Is this model mine?

by Pratyush Maini, Mohammad Yaghini and Nicolas Papernot

Are you worried that a machine learning model may be a stolen copy of your ML model? We answer this question with a new technique called dataset inference, introduced in our paper at ICLR 2021.

Our work starts by making the pessimistic but realistic observation that we cannot prevent model stealing. However, this does not mean we cannot detect when models are stolen. No matter how an adversary attempts to steal, their stolen model copy will contain information that originated from our dataset. Our insight is that most of the valuable intellectual property of the model comes from its training data. Our approach, dataset inference, thus attempts to distinguish a model’s behavior on points from its training set versus from unseen data. This distinction is measured on suspected stolen copies of our model to determine whether they contain knowledge exclusive to our data collection.

Here is a talk about our work which complements the rest of this blog post.

Why will anyone steal my ML model?

Training machine learning models from scratch is becoming increasingly expensive. This can be attributed to various factors that are involved in the training of a high-performing ML model — the high computation cost, the private dataset required to obtain high task accuracy, and intellectual contributions such as algorithmic or architectural novelty.

As ML models become valuable commodities, adversaries find (often financial) incentive to steal a victim’s model at a significantly lesser cost at their end.

How can an adversary steal my model?

An adversary may gain direct access to your knowledge and attempt to steal your model inconspicuously. This may happen when they gain (a) complete access to your private training data or (b) deployed model. This may happen due to insider access [1], or if you released your model (or data) for academic purposes (forbidding commercial use). For instance, if OpenAI were to release GPT-3 to the community, how could they ensure that no one later misuses it for commercial purposes?

A more indirect scenario is (c) model extraction. Here, a victim provides a machine learning service over the web, and an adversary repeatedly queries it on various data points. The answers to these queries allow the adversary to label a dataset subsequently used to train a copy of the model (for example, through distillation [2]).

Why is it impossible to prevent model stealing?

In scenarios of complete data access and model access, the adversary has all the ingredients required to train an alternate ML model: (a) either using the complete dataset or (b) via data-free knowledge distillation [3] once the entire model is available. It follows that model stealing is impossible to prevent if such access is unavailable.

The case of model extraction (c) is slightly more involved. To be of any commercial use (e.g., Machine Learning as a Service), a model owner must allow query access to legitimate users. However, adversaries may spoof adversarial queries to extract the model. They may also distribute their queries over multiple IP addresses to avoid detection. As a result, victims can not prevent such extraction attacks.

What is Dataset Inference?

Dataset Inference is a method to detect if a suspect model has been trained on a private dataset, or more generally, the knowledge contained within it. It builds on the observation that a model behaves differently when presented with training versus unseen (test) data.

More concretely, during training, the optimizer pushes the boundaries of incorrect class labels further away from points in the train set. This impacts model weights, and in turn, its predictions. However, the points in the unseen (test) set do not get a chance to modify model weights.

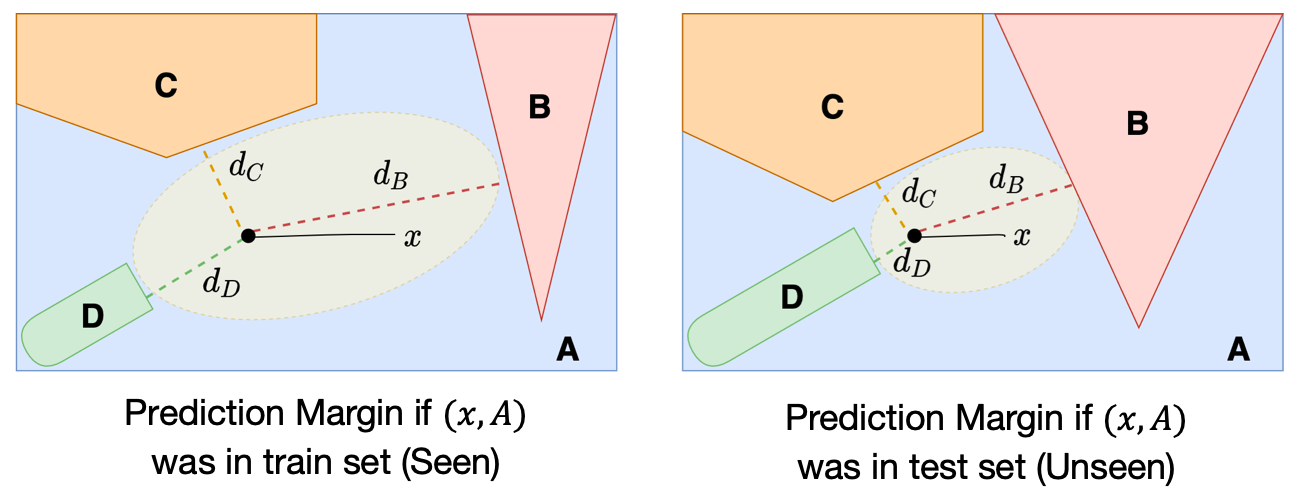

We illustrate this distinction below. On the left-hand diagram, the training point x (assigned label A) is further away from the closest points in classes B, C, and D than the test point x is on the right-hand diagram. We use prediction margin to denote the distance to incorrect classes, which we note, is also a measure of uncertainty of the model’s decisions.

If we repeat this experiment several times, we can simulate the expected prediction margin for points within the training or test (unseen) distribution. While the prediction margin for individual data points may have a very high variance, as an expectation over multiple samples drawn from the two distributions, we will observe a difference in the prediction margin (as a result of the optimization process). In our paper, we theoretically prove this result for the case of linear models. This allows us to test whether a model contains knowledge derived from the training set, as we explain next.

How do I resolve model ownership?

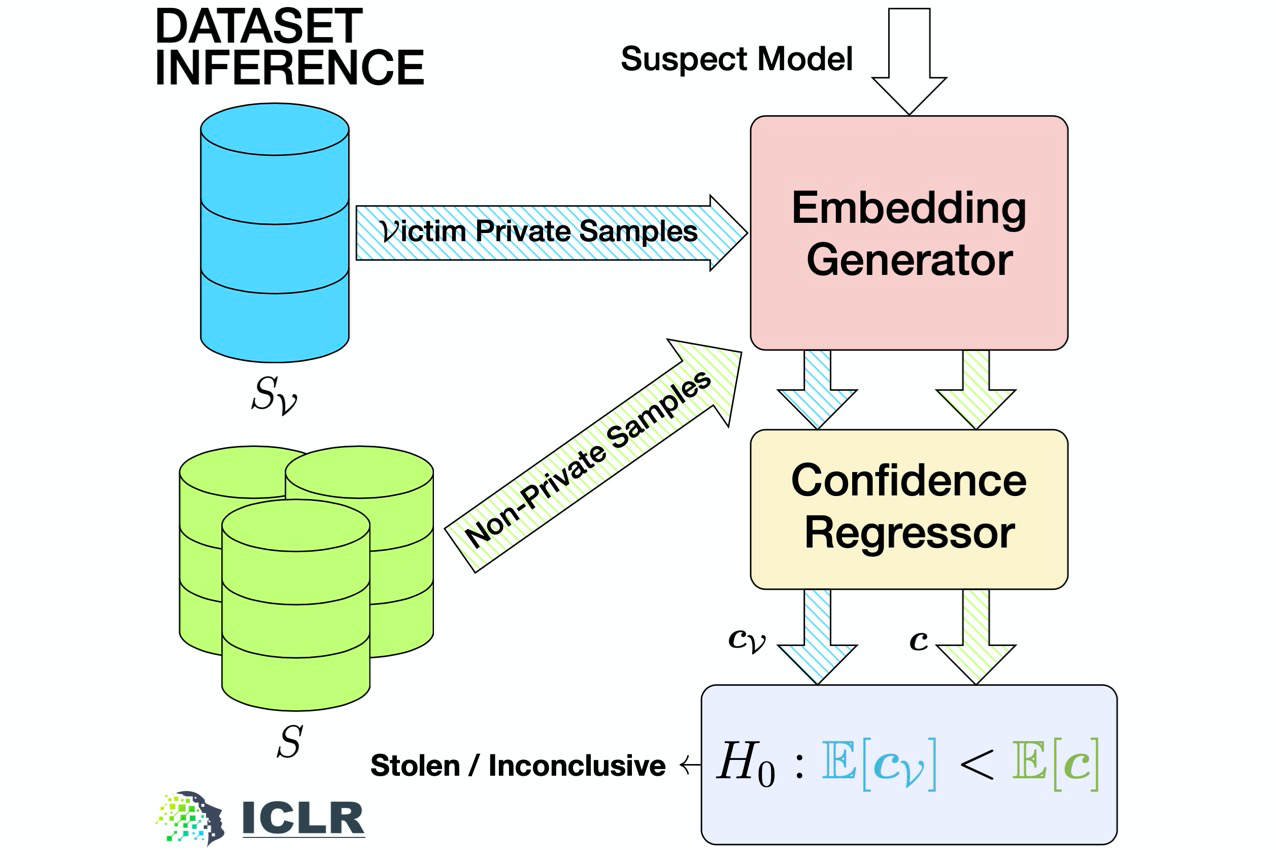

Dataset Inference calculates the prediction margin of seen and unseen points of a model and performs a statistical test to determine ownership. Estimating the prediction margin can be a non-trivial task in the case of deep networks. Therefore, we first create a feature embedding that reflects the prediction margin for a specific point for a given model. The feature embedding reflects how “far” the point is from the model’s decision boundary. The goal of the feature embedding is to encapsulate all the relevant information about a model’s behavior w.r.t. a given data point—such as what the prediction margin is and how the model’s local landscape around the point looks like. We then pass the feature embedding through a confidence regressor that gives a confidence score (or prediction margin) for each data point.

Given access to a suspect ML model, dataset inference takes the following 4-step process to check whether the suspect is stolen:

- Sample Inputs from your training set and an unseen set (e.g., the test set).

- Generate feature embeddings for points in both these sets with respect to the suspect ML model.

- Pass these embeddings via a confidence regressor to get prediction certainty.

- Aggregate these confidence samples and perform a one-sided t-test. The null hypothesis is that the mean confidence score for points in the unseen set is larger than that for points in the train set.

If the null hypothesis is rejected under the null hypothesis, we claim ownership of the suspect model. Recall that the p-value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true. We reject the null hypothesis when the p-value is lower than a previously determined significance value, for example, 1%.

Does Dataset Inference work?

Dataset inference shows promising results across different ML benchmarks such as CIFAR10, SVHN, CIFAR100, and Imagenet. We find that we can resolve model ownership by testing against a significance level of 1%, with fewer than 60 private samples of our dataset. We test the efficacy of our detection framework against 6 different attack strategies, including new adaptive attacks that are specifically designed to fool dataset inference. We find that dataset inference is robust to such attacks and performs well both in the white- and black-box settings.

Take-aways

- Plug and play solution that does not require overfitting or retraining. It can be used for models already deployed over the web!

- Dataset inference requires few private points to prove ownership (less than 60 points).

- Can be performed in less than 30,000 queries to the adversary.

- White-box access is not essential to dataset inference

- Does not have a trade-off with task accuracy

What Next?

Dataset Inference (dataset inference) takes a significant step towards resolving issues related to model ownership in machine learning.

- From a security standpoint, future work may benefit from training the confidence regressor on different types of potential adversaries. This will help make the overall pipeline significantly more robust.

- Another interesting direction is to expand dataset inference to tasks with discrete inputs such as NLP or RL settings.

- The ‘Blind Walk’ method proposed in this work can be used for black-box membership inference in future work.

- From an ML standpoint, dataset inference exposes a fundamental gap in the way we train our ML models. Even models trained on millions of images (example on ImageNet) end up behaving differently to points in the train versus an unseen set – indicating some form of memorization. This calls for alternatives to ML model optimizers that do more than maximize the boundary from incorrect classes.

- The confluence of dataset inference with uncertainty estimation or out-of-distribution (OOD) robustness presents an interesting direction: does the failure of dataset inference (inability to distinguish between a model’s behavior on training versus unseen data points) coincide with robustness to out-of-distribution samples?

- Finally, there lies an interesting array of possible future work by measuring how dataset inference fairs when models are trained with adversarial augmentation or differential privacy (DP)—i.e. scenarios where we do not optimize particularly for a given data point. Recent work [4] suggests that dataset inference should still succeed if models are trained with DP. As we argue in the paper, dataset inference essentially amplifies the membership inference signal. [4] shows that membership inference attacks still succeed in that setting, which bodes well for dataset inference.

Want to read more?

You can find more information in our main paper. Code for reproducing all our experiments is available in our GitHub repository.

[1] Tracy Kitten: ID Theft: Insider Access Is No. 1 Threat

[2] Hinton, Geoffrey E., Oriol Vinyals and J. Dean: Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. ArXiv abs/1503.02531 (2015)

[3] Gongfan Fang, Jie Song, Chengchao Shen, Xinchao Wang, Da Chen, Mingli Song: Data-Free Adversarial Distillation. CoRR abs/1912.11006 (2019)

[4] Klas Leino, Matt Fredrikson: Stolen Memories: Leveraging Model Memorization for Calibrated White-Box Membership Inference. CoRR abs/1906.11798 (2019)